Connoisseurship? Who decides what makes art great?

Connoisseurship is a slippery concept, but in simple terms a connoisseur is an expert judge. In the field of art, it means particularly the ability to distinguish the work of different artists, but can include knowledge of the physical characteristics of works of art (technique, condition, restoration), and their place in art history (period, style, school). The term was first used widely in the eighteenth century, often as a term of derision against new ‘experts’ who were usurping the traditional authority of artists to judge each other’s work. More contemporary academic art history has tended to reject connoisseurship, however, with a turn towards theory and social history.

Yet controversy about the relevance of connoisseurship persists. Regarded by many as elitist, there is often a cultural divide rather than a debate about the issue, with the two sides rarely engaging directly. Museums and art galleries tell you who painted the pictures on their walls. But they rarely explain issues central to connoisseurship – such as condition, style or, as the philosopher Roger Scruton stresses, beauty and redemption. Has the connoisseur been rightly consigned to the margins and, if so, who can help us judge fine art? Is the question of judgement really just down to how we feel about a picture? Do we lose something by not turning a connoisseurial ‘eye’ on art? Can anyone be a connoisseur? What makes connoisseurship a worthwhile approach to studying art? Or is connoisseurship the last refuge of the snobbish establishment?

What is connoisseurship? What is art? Is art merely a matter of taste? How do we distinguish false, bad or mediocre art from a masterpiece? What makes something qualify as art as opposed to kitsch? After all, regardless of how we assess art’s intrinsic value, art certainly has a price. Is everybody’s opinion equally valid?

Recommended reading:

-

80s Berlin, wild youth and their "bad art"

The Economist, Aug 18th 2015

THE 1980s are undergoing a revival in Germany. New-wave looks, garish party outfits, sequined glam mini-dresses and geometrical prints in neon were highlights of Berlin's Fashion Week in July. And "B-Movie: Lust & Sound in West Berlin", Mark Reeder's breathtaking documentary about West Berlin in the "frenzied but creative decade...from punk to the Love Parade", from 1979 to 1989, is currently luring cinemagoers. As Mr Reeder, originally from Manchester, said about moving to Berlin back then, "everything and anything seemed possible." -

Is any painting really worth $179m?

The Guardian, Tiffany Jenkins and Sarah Crompton

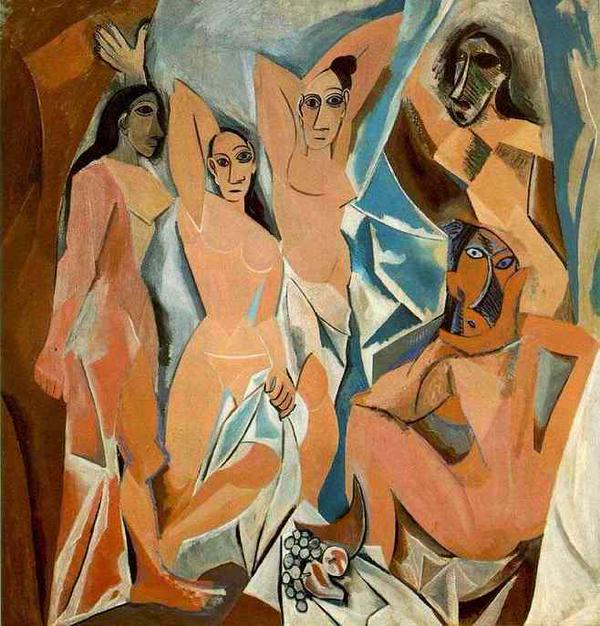

Picasso’s Les Femmes d’Alger (Version O) was painted in 1955 as the final work of a series inspired by Delacroix and painted in homage to Matisse. It recently sold for $179m at auction. Tiffany Jenkins and Sarah Crompton debate whether any painting is really worth so much money and in the process they disagree about the real value and purpose of art in society.

-

The case for old-fashioned connoisseurship

The Art Newspaper

The stifling of expert opinions is like having fully trained doctors who can’t make a diagnosis, says the art historian Bendor Grosvenor. -

Not in my name

Grumpy Art Historian

Bendor Grosvenor has written about his recent experience at a panel on connoisseurship hosted by the Yale Centre for British Art. It's worth watching; he makes a rousing and comprehensive case for the value of connoisseurship. But he is too polite about the response by Tate Britain's Martin Myrone. -

The Mark of a Masterpiece

The New Yorker, by David Grann

Every few weeks, photographs of old paintings arrive at Martin Kemp’s eighteenth-century house, outside Oxford, England. Many of the art works are so decayed that their once luminous colors have become washed out, their shiny coats of varnish darkened by grime and riddled with spidery cracks. Kemp scrutinizes each image with a magnifying glass, attempting to determine whether the owners have discovered what they claim to have found: a lost masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci. -

A Point of View: How do we know real art when we see it?

The BBC, by Roger Scruton

The world of art.... is full of fakes. Fake originality, fake emotion and the fake expertise of the critics - these are all around us and in such abundance that we hardly know where to look for the real thing. Or perhaps there is no real thing? Perhaps the world of art is just one vast pretence, in which we all take part since, after all, there is no real cost to it, except to those like Charles Saatchi, rich enough to splash out on junk? -

Art knows no boundaries, only influences

The Scotsman, by Tiffany Jenkins

Culture – high, low, and the everyday – has always been mongrel; it’s always been hybrid. It bears the imprint of other times and people, crosses history and geography, and contributes to the creation of something new. We should say no to self-imposed cultural immigration controls. Culture should know no borders.